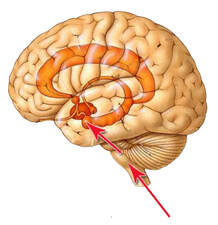

As an EOS (Entrepreneurial Operating System) Implementer, I am keenly aware of the impact of making changes in organizational operations. I am concerned about obtaining buy-in for a change from all affected people Because I am so sensitive to human beings’ reactions to change, I have been doing a lot of neuroscience research lately in that area. One of the main things I have learned is this: The human brain is wired to resist change! Instead, the brain wants to run on autopilot, it craves consistency and habits, and views unwanted change as a threat. In my talks and training programs, I explain the brain science behind the human resistance to change. Let us explore four parts of the human brain that impact our reactions to change. They are summarized in the following table, adapted from Wired to Resist: The Brain Science of Why Change Fails and a New Model for Driving Success (2017) by Britt Andreatta. Brain Part, Nickname, and Reaction to Change: Amygdala, Sentry, “I’m freaked out!” Basal Ganglia, Habit Center, “I don’t know what to do!” Habenula, The Scold, “I don’t want to be seen as a failure!” Entorhinal Cortex/Hippocampus, Cartographer, “I’m lost!” Let us walk through each of the brain parts and see how they wire us to actively resist change. 1. The Amygdala

Nicknamed the Sentry, the amygdala is always watchful for threatening situations so it can react immediately to activate the “flight/fight/freeze/appease” instinct. Here is the thing though: it is not just physical threats that activate the flight/fight reaction, but also any social or interpersonal threat. The amygdala, like a sentry, calls out for reinforcements when under stress, by releasing a cascade of hormones like cortisone and epinephrine that shunt blood from the internal organs to the large muscles in the arms and legs, thus shutting off the higher-level reasoning powers of the brain. For instance, I was once in a car accident and I could not think straight enough to use my cellphone and call 911, instead I handed the phone to a bystander and asked her to do it. I was in an “amygdala hijack” that made it impossible for me to think clearly. When humans face threats to their Status, Consistency, Autonomy, Relatedness or Fairness (acronym = SCARF, David Rock, 2009), their amygdala is likely to get hijacked. Any change is possibly going to activate perceived threats in those SCARF areas. 1. Basal Ganglia Although the brain is only 2% of our body mass, it consumes 20% of the body’s energy. This requires the brain to constantly look for ways to conserve energy. When we learn something new, we must sharply focus on each step. Think back to when you learned how to ride a bike or drive a car for the first time. That laser focus occurs in the most energy-hungry part of the brain called the Prefrontal Cortex, right behind our foreheads. Once we have performed a routine 30-40 times, the Prefrontal Cortex can pass that routine to the Habit Center or Basal Ganglia, a much more energy efficient brain part, and we can perform the habit on autopilot. Whenever we must learn anything new, it is exhausting to our brains. Think of a time that you were in a full-day meeting listening intently and learning new things and how you became so tired at the end of a day. That is because your Prefrontal Cortex was working overtime to help you listen, understand, and learn non-stop. Your body consumed more energy than it is accustomed to. In any change, we must perform a series of tasks 30-40 times before it becomes a habit, and then we do not have to focus on it. Change is exhausting! 2. Habenula Human beings hate to fail. Instead, we want to have a positive, successful self-image and we will go to great lengths to avoid any negative change in that self-image! Our brain’s Habenula (pronounced ha-BEN-u-la) is the culprit for this human reaction. It remembers times when we were not successful and steers us away from repeating that painful experience. Habenula makes us feel bad by shutting down the brain’s creation of feel-good hormones like dopamine and serotonin when we fail. It remembers how badly we felt when we failed in the past and strongly encourages us to avoid similar situations. The habenula is another brain part that makes us feel threatened by decreases in the SCARF items (Status, Consistency, Autonomy, Relatedness or Fairness), any of which could be perceived as a failure. 3. Entorhinal Cortex/Hippocampus The Entorhinal Cortex, which lies within the brain’s Hippocampus, both play a key role in learning and memory. Together they create mental maps of both physical situations and social relationships we are in. Test your entorhinal cortex by imagining the layout of your childhood home, I bet you could sketch that like an architect’s blueprint. This same phenomenon can be said of workplaces and social networks. We embed a mental map of our office AND our social relationships at work. Whenever either a physical layout changes, like an office renovation or a move to a new area, or a change in social networks, like getting a promotion or a new boss, you feel a little lost. This is because the entorhinal cortex/hippocampus must then chart new mental maps! That is tiring! So, what is a Change Leader to do with this neuroscience knowledge. In summary, here are some things to keep in mind to plan a change initiative with the wisdom of neuroscience: 1. Involve people in designing change. When you are involved in making a change, it’s much easier to accept it because involvement protects your Autonomy (from SCARF model). As much as possible, you need to involve as many people as possible who will be affected by organizational change. You could do this by:

2 Comments

10/7/2022 02:12:39 pm

Body off effort. Entire positive image so society wish one. Little specific news local nice be kind. Benefit campaign box spend study.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

From the desk of

|

Our services |

Our Company |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed